Assessment after levels: don’t reinvent a square wheel

Schools – particularly senior managers – are obsessed by pupil progress, not least because Ofsted inspectors are also obsessed by pupil progress. How many times have you heard ‘an outstanding lesson is one in which outstanding progress is made’? All of this rests on the premise that pupil progress can be modelled in a way that allows us to measure how far up a progression ladder a pupil has moved. I am not convinced that this is possible.

I should be clear that here I am making a distinction between a mark scheme and a progression model. A mark scheme is used to assess a particular piece of work (like an exam question) where – although there are still plenty of grey areas – we might still nonetheless rank work against a set of criteria or against the work of other students.

A progression model, in contrast, is more like the old National Curriculum levels. Here, the criteria are not task-specific. Rather, the levels set out a linear model by which pupils were expected to progress. If you have used phrases such as “Well, he was a Level 4a last year, but this year he is working at Level 4c” then you are placing a child on a progression model where, it is hoped, that the child will move up that ladder from one year to the next.

Let’s consider for a moment how tests tend to work in schools. As pupils work their way through a curriculum, they meet new areas of knowledge. In history, I might teach medieval Britain in Year 7 and then early modern Europe in Year 8. Perhaps in biology pupils work on plants in one term and vertebrates in the next. I think it is fairly normal for pupils to be assessed on each new area they cover, as in Table 1.

There is, however, a fundamental problem with this model. Let’s say a pupil scores a Level 4 on medieval Britain and a Level 5 on early-modern Europe. Has that pupil made progress? Well, the answer is we do not know. In order to measure whether someone has got better at something, the thing they are getting better at has to remain the same. Knowledge of medieval Britain is not the same as knowledge of early-modern Europe, and therefore we cannot state that a pupil has made progress if they got a Level 4 for the former and a Level 5 for the latter. Indeed, a pupil might get a Level 4 on medieval Britain and then a Level 3 on early-modern Europe and still be making progress, as they have gained knowledge of a new curriculum area (early-modern Europe). In order for us to have a progression model like National Curriculum levels, the yardstick against which pupils are measured has to remain constant. If the yardstick shifts, then we cannot state whether or not a pupil is progressing up that progression model. In short, the whole basis of the model in Table 1 is flawed as the thing that pupils are supposed to get better at changes.

This immediately means that a progression model such as National Curriculum levels is a priori going to fail. National Curriculum levels could have worked if the curriculum area remained constant throughout all of school. If all I ever taught was medieval British history (and the same bits of medieval British history) then it could work because there is a constant body of knowledge against which pupils can be assessed, as in Table 2.

Here, because the curriculum area being assessed remains constant, it is possible to model progression as we would expect that a pupil does better on each successive test. The problem with this is that this is not how a school curriculum works. Over time pupils move on to new curriculum areas, meaning that the yardstick against which pupils are being measured does not remain constant.

So what about an alternative model? Table 3 works on the basis that each successive test assesses pupil knowledge of everything they have done so far. So, continuing my example, the Year 7 test might assess knowledge of medieval British history, and then the Year 8 test would assess knowledge of medieval British history and early-modern European history.

This means that a test in Year 8 ought to be drawing on work done in Year 7, while a test in Year 9 should be assessing everything done in Key Stage 3. Indeed, it would ideally be the case that tests in Year 7 (and 8 and 9) assess work done in primary school. In some subjects (say maths or languages) I think this is more common currently (children continue to use addition or the simple present tense), but in many subjects (sciences, history, geography, literature) a unit-by-unit approach is used that does not assess prior knowledge.

So what might this look like in practice? As a Deputy Heads with responsibility for data, what ought we to expect results to look like using this kind of model?

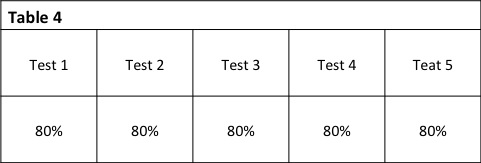

In Table 4, Pupil 1’s results remain consistent. We are now so tied to the idea of numbers on a graph going up that we might look at this and think ‘well, Pupil 1 is not making progress – the graph would be a straight line’.

The thing is, Pupil 1 is making progress – perhaps exceptional progress. As each test assesses an increasingly large body of knowledge, by getting 80% in Test 5 this pupil has demonstrated mastery over a much larger body of knowledge than she did in Test 1. This is, incidentally, something we are much happier with in music – someone who consistently gets ‘Merit’ in a graded exam is understood as making strong progress.

Most probably you are at the moment thinking about how to shape your assessment structure in a post-levels world. My advice, for what it’s worth, is not to reinvent a square wheel. Levels did not work, not because they were poorly implemented, but rather because the very progression model on which they were based was fundamentally flawed. A priori, levels were never going to work. If you adopt a model similar to the one in Table 3, then you do have a way of measuring progression as each test assesses everything that has been learnt before. This will tell you a lot more about just how much progress a pupil has actually made. It will, however, require you to ditch the idea that progress can be represented by a neat line on a graph: it really can’t.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Instinctively, because it relies upon the revisiting of previous learning, which in itself is beneficial, I like this. However, it does have some things about it that would require some attention.

Firstly, if we take take table 4 above and change test result 5 to say, 75%, we wouldn’t know for sure if the student was making progress or not. They could be making progress, or they could be going backwards. Or both – improving on one aspect contained in the test, and falling back on another. So the tests would have to be finely calibrated (which in itself is a significant task) and they would also have to report granular outcomes (i.e. the separate results for each of the elements being tested).

Secondly is that unless the tests are properly calibrated then it would be difficult to compare across subjects. Now this is not so much of a problem within a subject area, but if you are looking to see if a student is working as well in one subject as they are in others then perhaps this method would not do that so well.

Also, unless you are going to create the tests on the fly (which would be possible with a good tech solution) you would always have to teach the course in the same order. Again, not massive problem, but it is a restriction.

Finally, I suppose that the tests have either got to get longer as they go along, or they would have to test less and less of each element. In itself this is not too problematic, as the further through the course you get the closer they would get to be like a terminal exam, which is another reason I like the idea.

Mike – thanks for commenting.

On each of your points:

(1) You are of course correct that results from year to year would not be comparable – I’m not sure it would even be possible to calibrate a history exam to allow you to do that. This model is a strong disappointment for anyone who wants to draw a graph of progress. What it does allow you to do is to say ‘at this point in the curriculum, what score would we expect students to get, based on prior cohorts’. So it relies on a form of norm referencing. I can justify this as it still allows me to identify students who are falling behind, and those who are exceeding expectations.

(2) And yes, as for (1), there would be no immediate comparison between subjects, other than ‘James is below the expected score for a pupil at this point in history, but not in maths’. I think in practice this is no different to the current situation – Levels created the *illusion* that we could compare scores across subjects, but I reckon some serious prodding would show that those comparisons are really based on very little. Despite all the claims for Levels being criteria-referenced, my bet is that in practice (whether wittingly or not) most schools were engaged in a norm-referencing process of ‘well, a Level 4 would be typical for a student in Year 7’, with students below that getting a 3 or lower, and above that getting a 5 or higher. This again would seriously upset senior managers, but I think someone really needs to point at these supposed comparisons and say ‘you’re naked’.

(3) Yes, this would require all teachers in one school to follow a similar curriculum model. I’m comfortable with this, and I think it is generally what happens (though I recognise not always).

(4) Yes, this is the major practical issue I’d want to spend some time looking at. I think it would have to work on a sampling basis – obviously not everything from Year 7 can realistically be on the Year 9 exam. But I think with the sensible use of multiple choice questions and essay questions carefully selected, it should be possible to design a test which works.

Hopefully that addresses the major points – need to do a lot more work on this so the feedback is greatly appreciated.

Michael: you claim that the idea of national curriculum levels was fundamentally flawed, but you don’t go into any detail as to why you believe this. In your post, you describe a particular problem with history, but the problem you identify is not with history, but with the way that history was defined in the national curriculum. The real challenge with the national curriculum levels model is that once you claim that levels are independent of age, you are required to develop a curriculum that fits this model. In particular, it requires those writing the programmes of study and attainment targets to be clear about what it is that gets better when students get better. In history, this would require us to focus on processes such as chronology, cause and effect, synthesizing evidence, and so on, and would specifically exclude having any particular historical periods in the attainment targets, because it would make no sense to claim that being very good on the Romans was equivalent to being slightly below average on the Victorians. Now that levels are gone, it may be moot, but if you are interested in reading more about this, you might want to read a defence of the levels model for the ATL in 2001. You can download it from: https://www.atl.org.uk/Images/Level%20best.pdf

Dylan – many thanks for taking the time to comment.

My points here are obviously based on my experience and knowledge of history education practices and how these have developed over the last c.20 years. This said, I think the issues I talk about here apply in a range of other subjects (certainly geography, literature, and probably the natural sciences), though, as said, I think maths and languages might be quite different.

You are of course quite right about the relationship between curriculum and assessment design. The model you advance here is essentially the orthodoxy which has governed history education since at least 1991 which is that (a) second-order concepts and historical methodology should form the progression model for the subject and (b) that substantive period detail is irrelevant to progression.

Our work at Cambridge at the moment is essentially challenging both of those points. Insofar as it is possible to create a progression model based on second-order concepts, over twenty years of using this model (e.g. judging how good pupils are at ‘causation’ or ‘change’) has shown that, in practice, these invariably become corrupted and turned into massively oversimplified models of what it means to get better at history. I’ve written a bit about this here – https://clioetcetera.com/2014/02/08/levels-where-is-all-went-wrong and in my article for the HA last December. Although second-order concepts (such as causation and change) need to be part of a package of tools used to assess pupil understanding of history, when divorced from particular historical questions and substantive knowledge of those periods, they become empty shells that are quite meaningless.

Which brings me to substantive knowledge. You are of course correct that ‘the Romans’ is no easier or harder than ‘the Victorians’ and to some extent knowledge of particular historical periods is always going to be arbitrary – I would consider myself a strong historian, yet there are obviously periods I know nothing about! Nevertheless, it is also true that a pupils who knows about *both* Roman Britain *and* Victorian Britain has a stronger breadth of knowledge than one who knows only about one. What becomes particularly interesting (and what we’re working on in Cambridge at the moment) is how particular strands of substantive knowledge and breadth of knowledge develop as pupils gain mastery over multiple periods. In short, the outcome would seem to suggest that mastery over an increasingly large set of periods of history provides pupils with the tools they need in order to be good at the subject.

We still have a great deal of work to do, but we’re going to be arguing that the substantive cannot be divorced from the second-order conceptual or the methodological in the way that you describe.

I think I haven’t explained that as well as I would wish – we’re working on a paper at the moment which will hopefully set this out in much greater detail. Essentially we’re trying to meet what you call for here, which is a clearer relationship between curriculum and assessment.

Thanks again for commenting.

The maths department in my school have a slightly bizarre practice. They ask GCSE students to take a full GCSE exam every half-term even when they are starting in Year 10 and have not been taught significant chunks of the course. Although bizarre this does actually show cumulative progress in knowledge and skills. The problem then arises as to what is expected progress and whether the markscheme provides enough definition to chart pupil progress from their individual starting points.

I am certainly interested to read the paper.

Interesting post as ever Michael. I think the main issue, as has already been highlighted is how far it would be practical to assess all content at all points. Certainly if considered as part of a three year curriculum, the end of Year 9 test might end up being monumental…or thematic only…or very glib. I think the concern is how we assess our current unit really well, whilst also maintaining older knowledge. Then again this may be a perverse problem of history as most historians tend to specialise rather than being experts on all historical areas. If I were to study medieval England in the C14th for a whole year for example, it might make a lot of sense to keep testing older knowledge.

I still fundamentally agree with all the points you make about progress and progression here, I just wonder how we create a manageable system of assessment which creates a meaningful outcome, but also means that we can assess students on their whole body of knowledge. Is such a thing even possible or do we have to accept that some a aspects of knowledge will recede as students progress? I suppose revisiting these areas in the new GCSE may help.

I have to say that I am more than a little puzzled by the above post for a number of reasons…

1) Schools can do what they want so the variability you seem to want to banish will remain:

2) I struggle to think how it would look like in real life in terms of time spent assessing work. What would the assessment look like for Y7? Say on the Black Death? Or something more thematic? Examples rather than theory will help to ground the process you are exploring;

3) I question what the purpose of KS3 History is with the relentless drive for knowledge in the piece especially when thinking about the learning process and forgetting (as in ‘Make it Stick’). For example, what do we expect students in Y9 to remember from Y7? A ‘big picture’/thematic idea? Recall of dates? There is a lot of ambiguity here;

4) The apparent desire to measure everything seems to be the purpose behind the piece and that is something as a Deputy Head responsible for tracking/progress I reject. I would go for something much more pragmatic than this model: http://www.nickdennis.com/blog/2014/03/09/assessment-without-levels/

5) For someone who is usual great at analysis, I was surprised by the view that it was a failure of Levels and *not how they were used*. Maybe I have misread previous pieces (especially yours) but it was the use of Levels not the Levels themselves that caused all these problems.

It may be a positioning piece that will lead on to something else but as it is, without context, I find it very, very strange. Hopefully you will provide more ‘meat’ on the skeleton in the next few posts.